![Shams Irfan at Pakistani side of Wagha border.]()

Shams Irfan at Pakistani side of Wagha border.

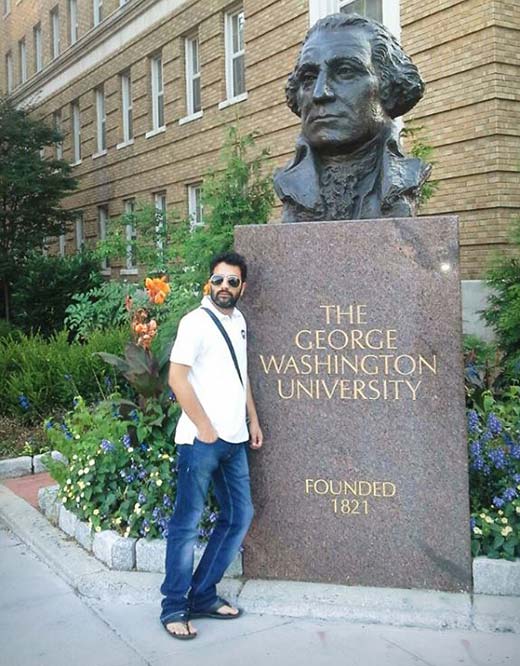

Shams Irfan

Carrying a thousand Salams (greeting) for the Pak Watan (Sacred nation) – from friends, relatives, neighbours, acquaintances, people I know and I don’t know – along with twenty boxes of Kashmiri Kehwa, and a few grams of Saffron, apart from my clothes, I set out on my journey. It was no ordinary journey; after all I was visiting Pakistan.

I was excited; at the same time a bit nervous too. For someone who has not been to Pakistan, or the land of “lawlessness”, as media portrays, being nervous was understood.

With same curiosity and apprehension, I set out towards Pakistan embassy located in central Delhi’s posh Chanakyapuri area.

It was almost noon when me and my cousin Iftikhar Ali Khan, a physiotherapist from Patiala, Punjab reached there. The winter sun was shining over blue dome of this beautiful edifice. After introducing ourselves at the main entrance, we were ushered into a small vacant waiting lounge.

After waiting for half-an-hour we were introduced to a visa officer named Ahmad. He looked more like a military man than a desk officer. It was hard to trace smile on his no-nonsense face. Still, I tried my best shot to expedite the process as we were already late. I told him, “I am from Srinagar.” Then after a short pause I added, “Srinagar, Kashmir.”

![Minar-e-Pakistan, Lahore.]()

Minar-e-Pakistan, Lahore.

He didn’t react. He took our passports and left without saying anything. After two hours or so another officer, this time a bit friendlier one, showed up with our passports. We were finally given visa.

But there was a small issue. We were not given police enquiry exemption. I told the officer that I am visiting Pakistan for a short duration and without exemption most of my travel time will be wasted in visiting police stations.

“The policy has changed. I am sorry I cannot help you,” he shot back without listening to my pleas.

“But I thought you treat Kashmiris a bit differently,” I asked.

“Sorry. But the policy is same for every Indian,” he said in an authoritative tone.

In the evening we left towards Patiala, and then next evening, after getting currency exchanged, we headed towards Amritsar. Next morning, December 18, 2015, we were at the Wagha border post. At the Indian immigration, after being given mandatory polio drops and a certificate that I had been administered them, I was finally in front of the immigration officer.

“You are from Srinagar,” he asked while looking at my passport.

“Yes, I am,” I replied.

“What do you do?” he asked.

“I am a journalist,” I said.

“Kiske khilaaf likhte ho (against whom you write),” he asked while looking at me.

![L to R: Abid Saeed Khan, Shams Irfan, Amir Iftikhar, Majid Saed Khan in Islamabad.]()

L to R: Abid Saeed Khan, Shams Irfan, Amir Iftikhar, Majid Saed Khan in Islamabad.

I said nothing but smiled at him. After completing the formalities, including checking of luggage etc. we were finally at the six-inch wide white line that divides India and Pakistan.

The officer at the Indian side, after taking a final look at our passports, said, “aap ja sakte ho (You can go)”.

For first one minute after crossing the line I was numb. I had no idea how to react. I was finally in Pakistan. But just to be sure I kept asking my cousin, “Are we there yet.”

The answer came when, a beautiful girl, probably in her late twenties, who was sitting behind the immigration desk, greeted me saying, “Salam Alaikum. Pakistan mai apka khairmakdam hai. (Greeting. You are welcome in Pakistan).”

Then after looking at my passport she said in a rather excited tone, “Aap Srinagar, Kashmir se ho? (Are you from Srinagar, Kashmir).”

I nodded my head in affirmation. Then with same excitement she added, “InshAllah jaldi azaad hoga. (It will be free soon).”

![With Anwar Aziz Choudhary (centre).]()

With Anwar Aziz Choudhary (centre).

After meeting my cousin, who had come to receive us at Wagha border, we were finally driving towards his home in Lahore city.

From the day me and my cousin planned our trip I was trying to sketch a rough picture of Pakistan in my mind. But all I could manage, mostly based on images seen on television and internet, was a lawless, insecure and a failed nation that is desperate to get rid of its “terrorist safe heaven” tag.

But as we inched towards Lahore city an altogether different world unfolded in front of me. I was looking out of the window with both excitement and curiosity. Excited to see twelve lane roads crisscross almost entire stretch, and curious to see so many foreign made vehicles plying on the roads.

Lahore is one of the most vibrant and lively cities I have been to so far. I could not agree more when my Pakistani cousin, after my arrival remarked: Jeeney Lahore nahi dekhiya oh jamiyah he nahi (One who has not seen Lahore is not born yet).

After meeting my uncle Saeed Ahmad Khan, who retired as chief accountant of Sohrab Cycle Factory, and other relatives whom I had only known through stories and Eastman colour pictures, we set out to explore Lahore.

It was already midnight when we left home for a drive around the city. I was apprehensive to leave at such late hours because of what I had read or heard about Pakistan. Our first stop was famous Lahore Food Street. There, night was still young, and people were arriving with their families for dinner. Yes, dinner. There is no set time for dinner in Lahore. You will find people coming out with their families at even 2:30 AM for catching quick bite or roadside snacks. It was like being part of an unending festivity that stretches the entire length and breadth of this beautiful historic city.

After tasting a few quick delicacies we went to the interiors of the walled city. Inside one of the 12 gates that once housed entire Lahore city, we ordered tea from one of the famous roadside stalls.

One thing that is common to people across the social and economic gulf is love for food. You will find bon appetite scribed all across their faces when they welcome you in their homes.

One of my cousins said that if you want to offend a Lahorei just tell him that you didn’t like the food he has served. It is the ultimate insult that you can inflict on a Lahorei.

The next day, we went to Androon Lahore (interior Lahore) to taste Taka Tak. It is a fine chop of lamb ribs, chicken heart and many other parts cooked, rather sliced, for an hour on a big pan with half a kg of butter. When the owner of the shop came to know that I am from Srinagar, Kashmir he put some extra butter as a mark of hospitality.

Later in the night, at around 2 AM, I and my Pakistani cousin drove to Bahria Town, some 20 kms from main city Lahore, to drop one of his friends at home. Bahria town is one of the many townships that have cropped up on the outskirts of Lahore in the recent past. Apart from a sprawling bungalow that allegedly belongs to PPP’s political heir Bilawal Bhutto, it houses upper middle class of Lahore.

At this odd hour most of the shops, showrooms, eateries and other stores were open and full of people. We stopped over outside one such shopping arena that houses a movie theatre. As my cousin was clicking picture I saw a group of young boys and girls, dressed up for their night out, step out of their car for late night show. I was told the last late night show starts at around 2:30 AM! Bharia town also houses the eleventh largest mosque in the world famous as Grand Jamia.

Next day, our day usually started afternoon as Lahore is to be enjoyed after the sundown, we visited Badshahi Masjid, Lahore fort and Minar-e-Pakistan.

What I sensed after hours of interaction with common Pakistanis – across the political, economic and social spectrum – is that there is an urge for setting things right. They (people of Pakistan) know that this is their moment of truth. Either they can set themselves free from the chains of corruption, sectarianism, extremism, hatred, and terrorism, or they can fall deeper into the bottomless pit. The choices are discussed at every eatery, on roadside tea stalls, inside busy markets places, in Masjids, schools, colleges, hospitals, virtually, everywhere. The common sentiment is: enough is enough, let’s just cut the crap and move on with living.

The sentiment found voice when few years back government in Punjab proposed a name change for famous Sir Ganga Ram Hospital located in Lahore. Sir Ganga Ram, a philanthropist who is often described as the architect of modern Lahore, has practically supervised the construction of almost every building worth a visit in Lahore. “There was a civil movement against the proposed name change,” said one of the volunteers whom I met at National College of Arts in Lahore.

In the aftermath of Babri Masjid demolition in 1992, Sir Ganga Ram’s Samadhi (tomb) was destroyed by miscreants including many temples in Lahore. Mention that and you could see a sense of guilt taking over almost every youngster’s face. “That was a maddening era,” said one of my cousins during our long interactions. “It was our cultural heritage. That should have been preserved.”

After offering prayers at Dr Sir Mohammad Iqbal’s (RA) tomb, located outside the main gate of Badshahi Masjid, me and my cousins went to National College of Arts (NCA).

Once inside NCA, you feel like entering an altogether different world; it is very much unlike Pakistan that you know or have been told about. It is one of the most progressive and liberal institutes of Pakistan. Founded by British as Mayo College of Arts in 1875, it has produced some of the greatest artists from Pakistan.

As one of my cousins, Majid Saeed Khan heads Films and Television Department of NCA, I had the privilege of interacting with faculty and the students. Though the interaction was brief, it helped bust a few myths.

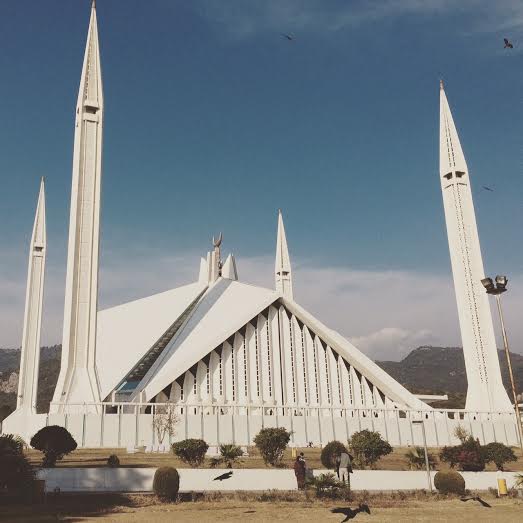

![At NCA, Lahore with Majid Saeed Khan, who heads Film and Televsion Department at the College.]()

At NCA, Lahore with Majid Saeed Khan, who heads Film and Televsion Department at the College.

First of all, India or the politics surrounding it is a non-issue for the younger generation; rather they love to talk about importance of art in a society, how one should look at ones cultural assets, how creativity should not have any limitation – religious, social or otherwise – how exchanging ideas or respecting diverse opinions help a society progress, why one must resist renaming of pre-1947 landmarks and much more. “India rhetoric is thing of the past for us. We don’t relate ourselves with that. Please!” said one of the faculty members whom I met at NCA.

A walk around the campus helps you understand why NCA, despite on-and-off criticism from Mullas, has evolved as a symbol of ‘new Pakistan’. Its walls are full of ideas/artworks that defy the dictates of a society that loves to live by self imposed censorship.

Later, I was shown some of the painting done by the students of NCA. It was really surprising to know that most of the paintings were already sold off. I was told that during annual exhibition of work done by the students, people from all over Pakistan visit NCA to appreciate art and buy paintings. It is one grand event people wait for. A students painting is usually sold somewhere between PKR 80 thousand to 5 lakh. And a film, if taken by a private satellite channel can even fetch students up to PKR 2 million.

The success of artists can be gauged by the fact that almost every drawing room I visited in Pakistan has a collection of oil on canvas. It is part of a legacy left by the Britishers who ruled the subcontinent for over 200 years. And Pakistan is still carrying that legacy gracefully.

On our way back from NCA we drove past a shop selling NATO goods. Located on the first floor, the shop’s windows displays military camouflages, gas masks, military boots, and other items customised for American army stationed in Afghanistan. One can buy a good quality protective suit meant for chemical war for just PKR 3000!

There is an interesting story behind how and from where these goods come from. But let us save it for some other time.

Journey to Islamabad

![On way to Islamabad, the capital city of Pakistan.]()

On way to Islamabad, the capital city of Pakistan.

After spending five days in Lahore, which by any case is insufficient to explore this magnificent city, I and my cousins set out towards Islamabad.

The 367 km motorway or M2 that connects Lahore with capital city Islamabad is one of the best roads that you can drive on. Such is the quality of M2 that on many occasions Pakistani Air Force has used this motorway as runway to land, takeoff and refuel its fighter jets! After an hour’s drive, covering more than one third (130 kms) of our journey, we stopped at one of the government facilitated refreshment areas. Interestingly, there is no construction on either side of the M2 right up to Islamabad. One can literally see the changing hues of landscape, vast fields, and green vegetable gardens zoom past while you comfortably cruise at 120 kms/hour. Every refreshment area has a fuel station, a Masjid, a highway police assistance booth, parking lot, KFC, music shop, eateries offering local cuisines, a free of cost rest room for anybody who feels tired, well maintained washroom, besides a shawarma shop. One can spend entire day at these restrooms. Throughout M2, special arrangements are made for truck drivers who ply during the night, including special rest rooms with comfortable beds.

After three and half hours, including the time we spent at KFC, we were in Islamabad. It was strange for a person like me who has to spend almost an hour daily to commute a distance of 12 kms from Pampore to Srinagar!

If Lahore is loud and lively, Islamabad is sophisticated and silent. You rarely find people honking behind you – it is considered uncivilized.

In Islamabad, we were hosted by my cousin Amir Mateen, a senior journalist and analyst who currently hosts a talk show on ARY News with Rauf Klasra.

Before arriving in Islamabad my cousin Abid Saeed Khan, an artist, painter and a freelance architect, sort of warned me that don’t expect the kind of life you experienced in Lahore here. Unlike Lahore, this city believes in indoor parties held inside well furnished drawing rooms where friends get together to talk politics, literature, art, theatre etc. The highpoint of these parties is food; yes food is central to even Islamabad’s life.

Thanks to Amir Bhai, who threw one such party for us, I got an opportunity to meet some wonderful people. The high point of the party was interaction with Anwar Aziz Chaudhary, a former federal minister in Z A Bhutto’s cabinet, who hails from Shakargarh Tehsil in Punjab, Pakistan. At the prime age of eighty five, Chaudhary Sahab, as fondly called by his friends, is one of the lively souls you can come across in life. As Choudhary Sahab was sharing anecdotes from his illustrious life, it was hard to tell when evening turned into night, and night into dawn.

For the occasion, cooks were specially brought from Peshawar to prepare Dumbah Dum Pukht. Dim light, delicious food, poetry recited by Choudhary Sahab, and a gathering comprising who is who of Pakistan’s media, what else can one ask for!

My Islamabad trip coincided with PM Modi’s dramatic Lahore stopover. The visit created a buzz in Pakistani media circle, evoking a mix of responses from people across the spectrum. This was probably the first time I found people talking about Kashmir. Though the sentiment viz-a-viz Kashmir is there, but it is not what they live and breathe all day. There are other day-to-day issues that dominate their daily discourse like any other society. But yes, when you tell them that you are from Srinagar, Kashmir, they treat you specially.

There is a visible urgency in people for peace. They have seen enough of bloodshed. You will hardly come across people, and by people I mean all across the social class, who get angry at a mere mention of India. In fact, they feel bad, or rather sad, the way India is reacting to issues related to minorities. “We have been there once. We have been intolerant too. But thank Allah that phase is over. What you see is a new Pakistan,” said a senior journalist. “We don’t want to go back while the world around us is in a fast forward mode.”

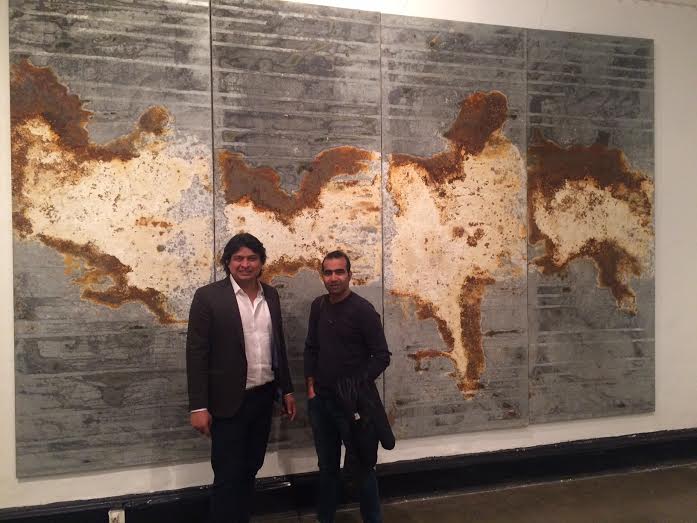

![Shah Faesal Masjid]()

Shah Faesal Masjid

Next few days I spent visiting landmarks in Islamabad including Shah Fesal Masjid, Margalla hills etc. In the meantime, I got a chance to attend a wedding in Islamabad. It was quite an experience to know that people strictly adhere to one dish norm in vogue after January 2015 Supreme Court of Pakistan ruling. At half past nine lights were dim inside the marriage hall signalling guests to wind up quickly as 10 PM is the official deadline for all functions. Just five minutes before clock struck 10, bride and bridegroom made their way out of the hall and drove off.

Unlike Lahore, after 10 PM, you will find only chemists and a few essential stores open, rest is all closed.

Reason. The city knows how to celebrate life within the four walls of their homes!

On our way back to Lahore, while resting my head on the back cushion of my cousin’s automatic V8 Mitsubishi Gallant, I began to rewind key points of my visit. The night lights zooming past us played on my mind like the strings of an electric guitar. But, despite a wonderful trip, there was something missing.

On the last day of our stay in Pakistan, my cousin took us for shopping to Liberty Market in Lahore. A semi-circular neat-and-clean market that buzzes with life round the clock, Liberty is a shopper’s delight. On the back side of the market, there are small open air eateries where you can relish your taste buds with chicken Shawarms, mutton kebabs, mutton and beef burgers, fish finger chips etc.

Overwhelmed by the emotions, I took out my cell phone and decided to capture the moment for future. As I was clicking pictures, a tall bearded man, clad in light brown kameez-pajama and a leather jacket, that he had complimented with a Peshawari cap, tapped me on my shoulder.

“Why are you taking picture,” he asked in a rather suspicious tone.

“I am a tourist that’s why,” I replied courteously.

“Where are you from?” he asked in the same tone.

“Srinagar, Kashmir,” I replied.

No sooner I mentioned Srinagar and Kashmir that his expressions changed suddenly; he shook my hands, and after clearing his throat, said, “Aap to hamare khaas mehmaan ho. Jitni photo khenchni hai khencho (You are our special guest. Take as many pictures you want).”

![With Sheraz Khan at Liberty Market, Lahore.]()

With Sheraz Khan at Liberty Market, Lahore.

Before I could react, he went from one shop to another, pointing towards me and telling the shopkeepers that I was from Kashmir.

Within no time I was surrounded by shopkeepers, shoppers, passersby and who not. They were shaking my hand, hugging me, inviting me inside their shops, asking me to have tea, dinner, snacks etc. with them. The man with Peshawari cap and leather jacket introduced himself as Sheraz Khan. He earns his living by selling ‘selfie sticks’ (PKR 1200 per piece), at Liberty Market. With tears in his eyes he told me that his ancestors are from a village near Gulmarg in Kashmir. His great grandfather, who was a hakeem by profession, migrated to what is now Pakistani Kashmir some hundred years back. Since then his family is living in Pakistan. “I wish I can go to Gulmarg just once. I want to see the land of my ancestors,” he said emotionally while people circling around us patted him in consolation.

As it was getting late, I took my leave from the crowd, and from Sheraz, promising him to return someday and talk to him about his ancestral land. “Insha Allah, Insha Allah,” he said and handed me a ‘selfie stick’ as a gift.

I refused to take the gift thinking that PKR 1200 mean a lot for Sheraz, but he was not ready to let me go without the gift, so was the crowd.

Finally, I took the gift as the crowd around us cheered with joy. Before I bid goodbye I insisted Sheraz Khan to have a picture with me to which he obliged happily. While leaving Liberty Market, I now knew what I was missing. It was the love of Pakistani people that I had to carry back, if not the soil – for which I have been receiving demands in my inbox from Kashmiri friends.

The next morning I and my cousin crossed back with a promise to visit again.

Goodbye Pakistan!

(The author was on a personal visit to Pakistan.)

I had always heard about the beauty of Kashmir. Snow-capped mountains, lush green forests, fresh meadows and a variety of flowers is how I used to picture Kashmir. Beside this, I was also aware that Kashmir is an active conflict zone.

I had always heard about the beauty of Kashmir. Snow-capped mountains, lush green forests, fresh meadows and a variety of flowers is how I used to picture Kashmir. Beside this, I was also aware that Kashmir is an active conflict zone.

Route to Pahalgam never stops fascinating you. It is not only ‘picture perfect’, but equally intriguing, making one feel: whether it is meeting the fate of Punjab. Such is the flip the highway down the south Kashmir is getting.

Route to Pahalgam never stops fascinating you. It is not only ‘picture perfect’, but equally intriguing, making one feel: whether it is meeting the fate of Punjab. Such is the flip the highway down the south Kashmir is getting. The 120 odd km 3-hour drive from Srinagar took us along winding roads with the river Lidder flowing beside us and prayer flags fluttering at intervals.

The 120 odd km 3-hour drive from Srinagar took us along winding roads with the river Lidder flowing beside us and prayer flags fluttering at intervals. One fine morning I and my cousin, Nousheen, who is more a friend than a cousin, decided to refurbish an old ancestral structure, located near our home and convert it into a shop.

One fine morning I and my cousin, Nousheen, who is more a friend than a cousin, decided to refurbish an old ancestral structure, located near our home and convert it into a shop. The following days proved even painful for entire Kashmir, especially for those living in downtown who had limited access to essentials. In order to feed their families people used to visit Sabzi Mandi in wee hours and get stock of vegetable that would last weeks. The spirit of unity made people share things with those who were less fortunate and economically weak. As houses are constructed in close proximity in old city, distributing eatables among the needy was easy.

The following days proved even painful for entire Kashmir, especially for those living in downtown who had limited access to essentials. In order to feed their families people used to visit Sabzi Mandi in wee hours and get stock of vegetable that would last weeks. The spirit of unity made people share things with those who were less fortunate and economically weak. As houses are constructed in close proximity in old city, distributing eatables among the needy was easy. I remember sitting in the third storey, alone, engrossed in my thoughts, feeling helpless. A week later, I and my cousins visited Zakura to mourn our aunt’s death. On our way back, we saw people sitting on the roadside, keeping a vigil, trying to stay together as they feared CRPF might attack their houses at night.

I remember sitting in the third storey, alone, engrossed in my thoughts, feeling helpless. A week later, I and my cousins visited Zakura to mourn our aunt’s death. On our way back, we saw people sitting on the roadside, keeping a vigil, trying to stay together as they feared CRPF might attack their houses at night.